My choice of music probably dates me, but that’s okay: I admit that I am a child of the 60’s. Click on the arrow to listen because I want you to have this song on your mind as you read my last post. I imagine that Max’s mother is singing this song to him as he returns home from his adventure:

“Wild thing…you make my heart sing…

You make everything

Groovy

I said wild thing…

Wild thing…I think I love you

But I wanna know for sure

Come on, hold me tight

I love you.” Etc

These are not the most complex of lyrics, but then, the message is simple: Wild thing…I think I love you. In Where the Wild Things Are, poor Max feels so unloved. So he envisions another world where he can have a little fun, live by his own rules, and forget about his troubles.

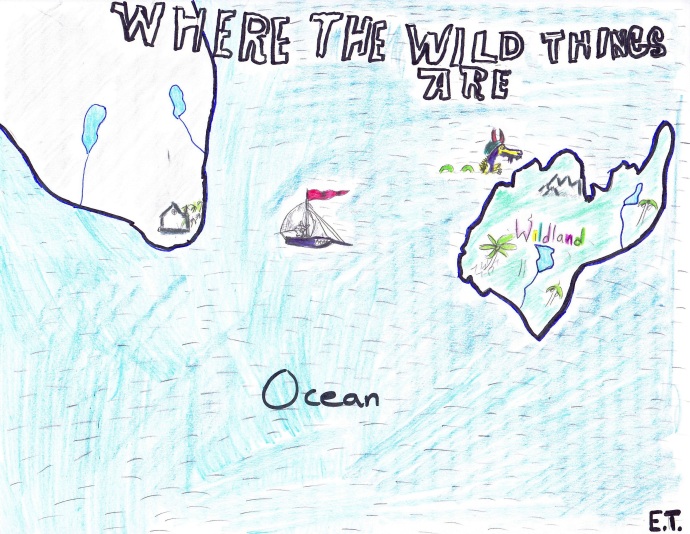

Again, there’s no map to guide us to this world. Max’s journey is the hardest one to imagine because it’s such a personal, private, and inner odyssey. But nephew ET has stepped into the breach, and he insists that he’s got this covered. So…hand-drawn map. Check. Amateur guide. Check. Novice cartographers. Check. No problem (well, except that there is no compass either!)

A New Map of Where the Wild Things Are (2012)

| Map Name | Where the Wild Things Are |

| Cartographer | “ET” |

| Artist/Colourist | “KLEW” |

| Publication Date | July 4, 2012 |

| Physical Description | Hand lettered, coloured in pencil crayon. Relief shown by hachures. |

| Size | 21 cm wide x 28 cm high |

| Compass | Not noted |

| Cartographic Elements | On Wildland, Some topographical details, locations of bays, lakes, and rivers, some settlements, mountains, ocean showing waves. Other landmass devoid of any elements except for two rivers and lakes. |

| Decorative Elements | Ship named Max with one small boy at the helm, sea monster, Wildland shows plants such as pineapple or palm tree. On mainland is a small house with coniferous trees. |

| Nomenclature | Sparse: Island named Wildland; unidentified Ocean. Other land mass unnamed. |

| Donated to | ImagiNation Blog July, 2012 |

*Thanks to Professor Found, of the Faculty of Environmental Studies and the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies, York University, whose map collection informed my knowledge of displaying information about maps July 23, 2012.

Interview with the Cartographer

Nancy: Why is there no compass on your map?

ET: I thought Max was wild and that he didn’t need a compass just because of the kind of person he was.

Nancy: How did you do the lettering?

ET: I took it from the book because it would make the map look more like the book. Wildland is more colourful because that is where the adventure begins.

Nancy: Why do you think the author didn’t include a map?

ET: Because the author wants you to come up with your own story. The author wanted the reader to make it about his or her personal story, not just what he put on paper.

During a prolific sixty-five year career, Maurice Sendak wrote or illustrated more than 100 books and received numerous awards for his work. He was a first-generation American, born to poor Polish-Jewish immigrants. He lived through the Depression, and his family experienced unspeakable loss when their relatives in Europe were annihilated in the Holocaust. Maurice (or Morose as some people called him) used his own memories of childhood as inspiration for his work. He modelled his “Wild Things” on relatives, who visited him when he was ill (Wood 1) and wanted to “eat him up” (Rosenbach Memorial 1). His deep interest in childhood was “fuelled by going into therapy.” Because he believed that “the traditional portrayal of childhood was inaccurate, … he sought openly to confront children’s everyday fears and frustrations” (National Post 1). He examined both subjects when he wrote Where the Wild Things Are in 1963. You can listen to Sendak talk about his childhood and Where the Wild Things Are with NPR’s Terry Gross by clicking here.

There is no doubt that young Max is upset and frustrated. He has been mischievous, “his mother called him ‘WILD THING!’ and Max said ‘I’LL EAT YOU UP!’” (Sendak 5). Having argued and talked back to his mother, she sends him to bed without his supper. From the look on his face, it is easy to see that he is angry. His mother doesn’t consider his feelings or ask him what’s wrong—she just threatens him. In his life, he has no say, no power, and no agency. However, he does have the imagination to create a world where he can have all of those abilities. The trip that Max then takes is an emotional one and is a direct result of his agitated state. He doesn’t want to dwell on what just happened; he just wants to get away. So he calls up “an ocean…with a private boat…and he sail[s] off…to where the wild things are” (Sendak 13, 15).

In Deconstructing the Hero, Margery Hourihan suggests, “The wild things symbolize both the external ‘others’ and the hero’s inner fears and passions” (Hourihan 107). In this wild land, Max comes face to face with the monsters. Here, he wants to conquer and control the “wild things” because he lacks this ability and has no control over his own life. Here, where the wild things are, he has autonomy, he has power, and he has authority. He dominates the monsters with his eyes, with his command, “BE STILL” (Sendak 19), and with his crown and sceptre. During his short but enjoyable time with the wild things, Max wonders, “What do they have that I don’t?” Well, they know how to listen and how to control their emotions. They know how to howl at the moon, at the insanity of the world, and at the unfairness of life. They know how to live in the moment. They can laugh, have a good time, not take things too seriously, revel in the rumpus; and they can love. These are skills or qualities that Max lacks, but they are necessary if he is going to grow up and navigate successfully in the adult world. Hourihan states, “We must all make the journey from childhood to adulthood and overcome the disabling doubts and terrors that beset us on the way” (Hourihan 107). In a way, Where the Wild Things Are is a healing text and could be part of what Freud calls “‘the talking cure’” (Crago 181). Hugh Crago says, “The basic idea of bibliotherapy is to…have a ‘reading therapist’ [suggest] a story which in some way bears on [a specific] problem” (Crago 184). This book, used as bibliotherapy, could help parents and children confront and discuss the “dark, dangerous and frequently rebellious” world of childhood (National Post 1).

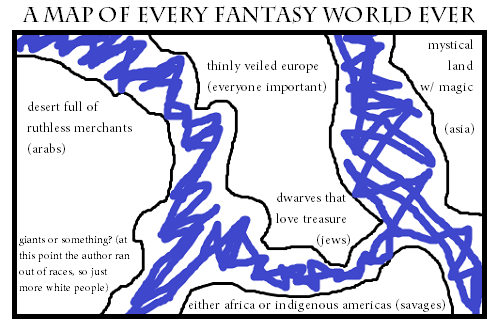

As ET said in the interview, it’s personal: everyone’s journey is different. It is difficult to plot or map a journey of emotional growth and realization. We each have to find our own way. Well, even without a compass, we did it! We found our way ‘there and back again’. Thank you for joining KLEW, ET, and me on this journey into ImagiNation. I hope you have enjoyed the adventure and that you will look on every book (with or without a map) as being full of potential and possibility. And remember, as Alexander McCall Smith says, “Regular maps have few surprises: their contour lines reveal where the Andes are, and are reasonably clear. More precious, though, are the unpublished maps we make ourselves, of our city, our place, our daily world, our life; those maps of our private world we use every day; here I was happy, in that place I left my coat behind after a party, that is where I met my love; I cried there once, I was heartsore; but felt better round the corner once I saw the hills of Fife across the Forth, things of that sort, our personal memories, that make the private tapestry of our lives” (Smith, Love Over Scotland).